Ötzi the Iceman: The famous frozen mummy

Over thirty years ago, they found Europe’s most famous mummy. It was lying face-down in the ice near a lake high up in the Ötztal Alps, between Austria and Italy.

Because of the cold, wind, and sun for over 5,000 years, Ötzi the Iceman was naturally preserved. He became very famous worldwide, with many books, documentaries, and even a movie made about him. They reconstructed his life in ancient Europe and how he died violently.

Nowadays, Ötzi is looked after by researchers at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy. They keep his body in a special cold room at a constant temperature of -21.2 degrees Fahrenheit. Every few months, they spray his remains with sterile water to make sure he stays wet and preserved, just like how he was found in the ice.

Every year, around 300,000 people visit Bolzano to see the ancient Iceman through a thick glass window. They can peek into his icy room and marvel at him. Scientists also want to study Ötzi because he’s amazingly well-preserved. He lived way before Europe’s first cities and even before Egypt built its first pyramid. It’s a rare chance for scientists to learn about life from so long ago.

“Ötzi is, in my opinion, the most thoroughly studied human body in the world,” says Oliver Peschel, the forensic pathologist from Munich who looks after Ötzi.

After three decades of research, here’s what we’ve learned about the life and death of the Iceman—and what more we might uncover in the future by studying his remarkable remains.

Who was Ötzi?

Ötzi was slender, not very tall (5’2”), and approximately 46 years old at the time of his death. He favored his left hand and wore shoes sized like a U.S. men’s 8. His eyes, still intact in their sockets, were previously believed to be blue, but recent genomic analysis showed they were actually brown. Albert Zink, who leads the EURAC Institute of Mummy Studies in Bolzano, where much of the key research on Ötzi has been conducted, confirms, “We found out he had brown eyes, dark brown hair, and a typical Mediterranean skin tone.”

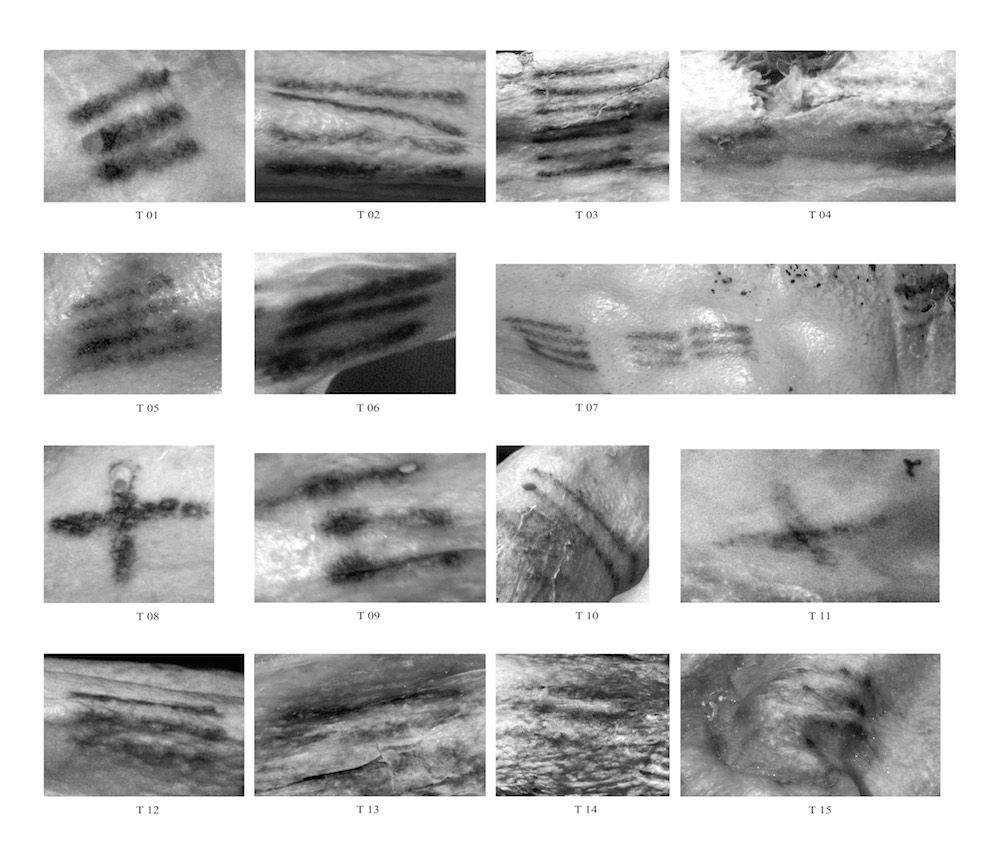

The Iceman had type O blood and couldn’t digest lactose. He also had a rare genetic issue where his 12th pair of ribs didn’t develop. He dealt with dental issues, stomach worms, Lyme disease, and had sore knees, hips, shoulders, and back. His 61 tattoos lined up with areas where his bones and joints were worn out (and matched up with modern acupuncture points). Ötzi had broken ribs and his nose before, and lines on his fingernails showed he went through periods of stress, likely due to not getting enough food, in the months leading up to his death. He was prone to heart disease, and a CT scan confirms he had the oldest known case of it in the world.

Based on carbon dating, Ötzi lived roughly 5,200 years ago (3350–3110 B.C.)

Who were his people?

Ötzi’s DNA shows he belonged to a group of ancient farmers who moved from modern Turkey to Europe 8,000 to 6,000 years ago. They replaced the hunter-gatherers who lived there before. His mother’s genetic background isn’t seen in people today, but his father’s line can still be found in groups from Mediterranean islands, like Sardinia.

What he wore

When they found Ötzi, he was wearing just one shoe, but they found many of his things nearby. His pants and coats were made from sheep and goat hides. His shoes were filled with wild grass and had laces made from auroch leather. And his hat was made from the fur of a brown bear.

What he carried

As Ötzi journeyed through the Ötztal Alps, he carried a wooden backpack and a deerskin quiver with 20 arrow shafts, but only two had arrowheads. His flint dagger was sharpened using a tool made from lime tree wood and a fire-hardened antler tip. He also had a birch bark container, like the ones still made in the region today, which held smoldering charcoal wrapped in fresh maple leaves, helping him start a fire quickly.

Ötzi had a very special copper axe, which was a key discovery. It had a blade made from almost pure copper, attached to a handle of yew wood using cow leather and birch tar. This axe was a symbol of wealth back then. Finding it helped researchers realize that the European Copper Age started much earlier than they thought, extending back a thousand years.

His last meal

Before Ötzi died, he ate a big meal including einkorn wheat, red deer, and ibex. Researchers only found his stomach after 18 years, using a CT scan in 2009. It was tricky to find because it had moved under his ribs to where his lower lungs are.

His death

Ötzi had a cut between his thumb and first finger on his right hand, showing he was stabbed a few days before he died. It looked like he tried to grab the blade, so it was probably a defensive move. That wound was still healing when he was shot with an arrow that hit an artery in his back left shoulder. He might have sat down and tried to pull out the arrow, but he likely bled to death within minutes and couldn’t reach it in time.

Ötzi had a lot of bleeding in his brain, but experts aren’t sure why. Did someone hit him on the head? Did he fall and hit his head on a rock? Peschel, the expert, doesn’t think there’s enough proof for either of these ideas.

How Ötzi was naturally mummified

Experts studied the pollen and the leaves Ötzi had with him and figured out he died in early summer. Some think that the warm summer winds dried him out, but Peschel disagrees. He believes it was the freezing cold of the high mountain pass that kept Ötzi preserved. Usually, the brain and other organs would turn to liquid a few days after death, but because of the freezing cold, Ötzi’s brain froze quickly, preserving it in a dry form.

What his gut says

Many studies have been done on Ötzi already, and more are coming. The Institute for Mummy Studies has now sequenced Ötzi’s genome, and they’re looking into his gut microbiome. They want to understand all the bacteria that lived in his stomach and intestines.

Scientists are interested in Ötzi’s gut bacteria because it’s connected to our health. One study found that Ötzi had three strains of a bacterium called Prevotella copri. Normally, people around the world have different strains of this bacterium, but many Westerners only have one. This can reduce the variety of bacteria in their gut.

Ötzi’s gut contained a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori, which is found in about half of the world’s population today. For some people, this bacterium can cause severe health issues. The type of H. pylori Ötzi had suggests that the strain common in Europe today is a mix of Asian and African strains, with the African strain arriving after Ötzi’s time. This finding impacts the debate about whether H. pylori is a natural part of our gut bacteria or should be treated with antibiotics. Another study found a harmful strain of another bacterium, Clostridium perfringens, in Ötzi’s gut. This bacterium can cause food poisoning.

A better, greener Ötzi

The city of Bolzano wants to make a new museum for archaeology soon. They want to put both Ötzi and more Tyrolean artifacts in it. They also want to make the system that keeps Ötzi cold work better, so it doesn’t use too much energy. They have a backup system ready too, just in case the main one stops working.

Imitating Nature

Researchers at the Institute of Mummy Studies are studying a chamois, a kind of goat-antelope, found in the same area as Ötzi. Even though it’s only a few hundred years old, it’s preserved a lot like Ötzi. Scientists are changing the humidity and temperature where the chamois is kept to see how it affects preservation. They’re also studying the microbes on and inside it to understand better how they play a role in preservation.

The unimaginable research of 2050

New technologies will help uncover more of Ötzi’s secrets, and they’re likely to come. In 2012, scientists decoded his 5,000-year-old genome just as DNA sequencing was getting better and cheaper. Zink says he never imagined researchers could reconstruct Ötzi’s microbiome, but now with rapidly advancing methods, they can gather much more information.

In the future, researchers might look into how Ötzi’s body worked, like studying the proteins, fats, and enzymes in his tissues to learn about his immune system. But right now, analyzing proteins in ancient samples is really complicated.

Meanwhile, the people taking care of Ötzi have to balance letting scientists study him with keeping him safe. The museum gets about 10 to 15 requests each year to study Ötzi. Experts from different universities and the museum look at each request carefully. They only take small samples from the surface for microbiology tests about once a year, and they hardly ever thaw him out. The last time they did that was in 2019.

“We can’t predict what kinds of science will be possible in 2050,” says Peschel. “So it’s important to keep Ötzi in good condition for future research.”

Also read,

5 UNSOLVED Disappearances That Shocked Our World