Mountain Man Jim Bridger

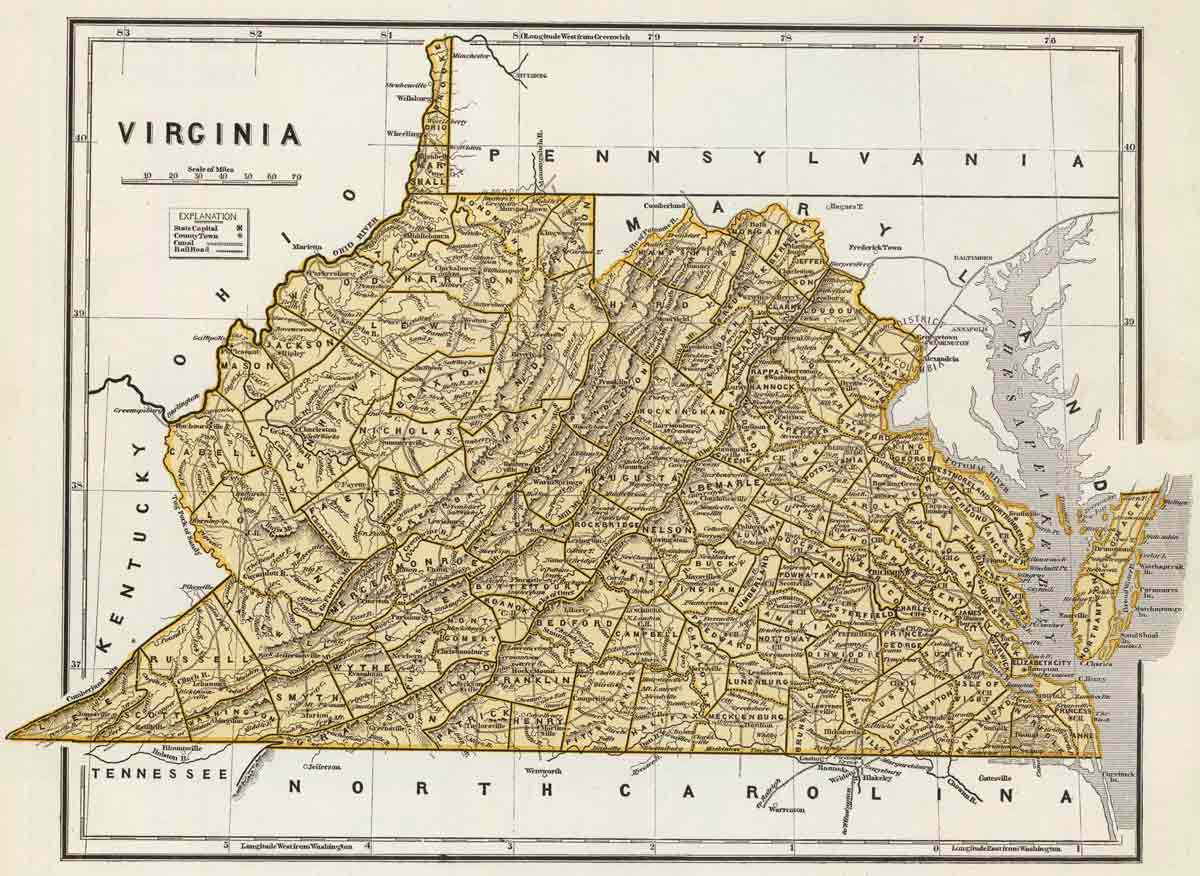

Mountain men were key figures in shaping the American West. They lived boldly, driven by the idea of Manifest Destiny, seeking freedom, adventure, and sometimes even a bit of fortune. Among them was James “Jim” Bridger, born in Virginia in 1804. Bridger was a skilled trapper, fur trader, explorer, and guide. He founded Fort Bridger on the Oregon Trail, which became a busy hub, and inspired many to embark on their own western adventures.

1. Jim Lost His Family in the Span of Two Years

Details about Jim Bridger’s early life are unclear due to limited records from the time. What we do know is that Jim was born in Virginia to hardworking parents. His father, either named Patrick or James Sr., was a farmer, and his mother, Chloe, ran an inn. Jim had an older brother, a younger sister named Virginia, and possibly a baby brother who died young. The family lived an ordinary life, surviving through their hard work. However, between 1815 and 1817, Jim lost both parents and his brother(s) to an unknown illness, leaving him and Virginia as orphans. At just 13 years old, Jim started working as a ferryboat operator and apprentice blacksmith to support himself, while Virginia went to live with an aunt.

2. He Was the First White American to See the Great Salt Lake

Jim Bridger spent part of his early life working for William Ashley’s fur company. In the winter of 1824, the group was camped near the Upper Bear River, in what is now Utah. A disagreement arose about the river’s course, so they split into smaller groups to explore. Bridger followed the river and discovered what we now call the Great Salt Lake. Due to the salty water, he believed he had reached the Pacific Ocean. While Bridger is credited as the first white American to visit the Great Salt Lake, Indigenous people had been visiting it for centuries before.

3. He May Have Abandoned Hugh Glass

Hugh Glass was another famous mountain man whose story became legendary after he survived several life-threatening challenges. He and Jim Bridger may have worked together, with Bridger possibly playing a significant role in Glass’s incredible tale.

Hugh Glass was part of Ashley’s fur hunting expedition, known as the Second Ashley Expedition, which left St. Louis in 1823. The group faced many dangers, including attacks from Indigenous groups. While hunting for food, Glass came across a mother bear and her cubs. The bear attacked him, nearly killing him, until his companions arrived and killed the bear. Severely injured, Glass hovered between life and death for several days. The group’s leader, Andrew Henry, decided they had to move on for the safety of the others. He asked for two volunteers to stay behind, wait for Glass to die, give him a proper burial, and then rejoin the group. The volunteers were recorded as John Fitzgerald and a young man named “Bridges.” Many historians believe that “Bridges” was likely Jim Bridger, given the timing, his age, and his work with the company.

Fitzgerald and Bridges (likely Jim Bridger) stayed with Hugh Glass for a few days, but Fitzgerald convinced Bridger that they needed to leave, fearing another Indigenous attack. Assuming Glass would die soon anyway, they took his belongings, including his rifle, and left him by a spring. Against all odds, Glass survived and trekked hundreds of miles back to civilization. He set out to find the two men who abandoned him, but it was later revealed that he didn’t hold a grudge against Bridger, believing that Fitzgerald was the one truly responsible. Glass reportedly told Bridger, “For your youth, I forgive you.”

4. He Probably Doomed the Donners

As the fur trade declined, Jim Bridger and his partner Louis Vasquez set up a trading post along the Oregon and California Trail, where the Mormon Trail branched off to Utah. Located in Wyoming, the original fort was just two 40-foot log houses and a horse pen. Over time, it grew into a larger compound and became a station for the Pony Express, Overland Stage, and the telegraph in the 1860s. Later, the U.S. Army used it as a garrison.

One group of exhausted travelers who stopped at Fort Bridger in 1846 was the ill-fated Donner Party. They became infamous in American history due to a disastrous journey that led to the deaths of 42 people and left many others traumatized. The group got trapped in the Sierra Nevada Mountains after trying to take a route called “The Hastings Cutoff.” This route, promoted by Lansford Hastings, brought more business to Fort Bridger. However, Hastings had never actually traveled the route himself, and it turned out to be longer and more dangerous than the main trail.

When the Donner Party reached Fort Bridger, they expected Lansford Hastings to meet them and guide them through the cutoff. However, Hastings had already left with another group. In his absence, Jim Bridger reassured the Donner Party leaders that the route ahead was easy, with plenty of water and grass. This was untrue, as Bridger had no real knowledge of the conditions. He was motivated by the hope that a successful journey would bring more business to his fort. Louis Vasquez also played a part in the deception by withholding a letter addressed to one of the Donner Party leaders, James Reed. The letter, written by a friend named Edwin Bryant, warned of the difficulties ahead and advised them to turn back. The Donner Party never knew the letter existed.

5. He Was Known for His Tall Tales

Jim Bridger was well-known and loved for his tall tales, sharing stories of incredible sights and adventures he had experienced. Many of these stories were exaggerated, but they entertained visitors at his fort. One of his favorite tales was about Yellowstone, where he claimed the petrified forests were filled with “petrified birds singing petrified songs.” In another story, he described a lake with cool water deep below but boiling water on top, claiming that the fish he caught were cooked by the time he reeled them in for dinner. When asked about his storytelling, Bridger would shrug and say he didn’t think it was right to spoil a good story just for the truth.

6. All Three of His Wives Died in Childbirth

Jim Bridger had three wives during his life, all of whom were Indigenous women. His first wife, Cora Insala, was the daughter of the Chief of the Flathead Nation. They married in 1835 after knowing each other for some time. They had three children together, but Cora sadly passed away from complications after childbirth in 1845.

Bridger’s second marriage was in 1848 to a Ute woman whose name has been forgotten. She also died in childbirth after having their only child.

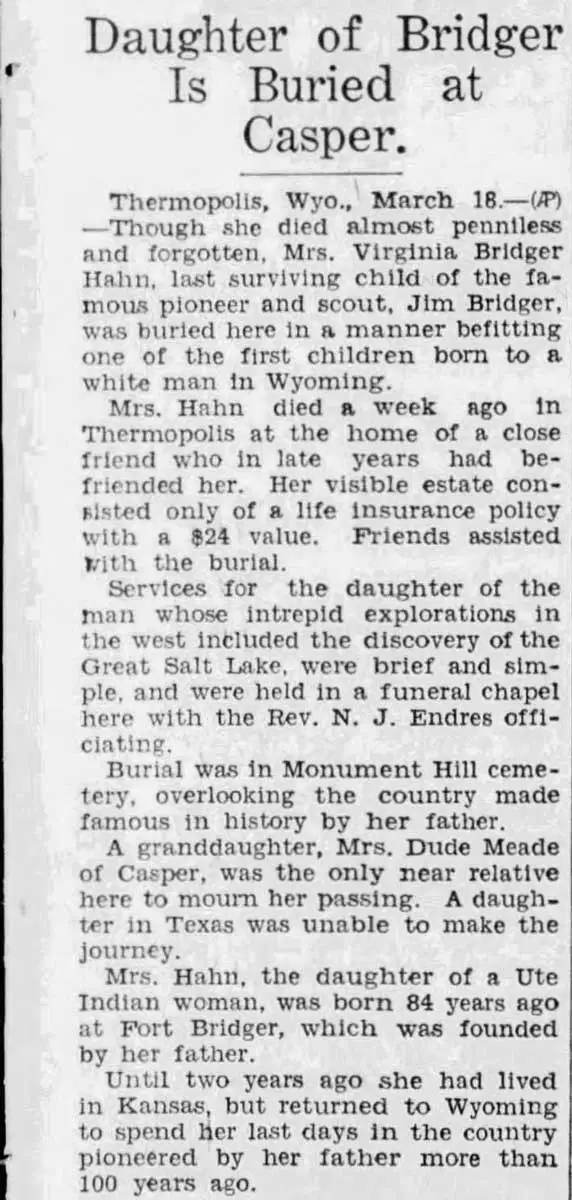

His third wife, Mary Washakie, married him in 1850. She was a Shoshone woman who had been Jim’s housekeeper for about two years, and he was good friends with her father. Tragically, Mary died in childbirth in 1868, leaving Jim with two children from their marriage. In total, he had six children. He lost his eldest daughter, Mary Ann, after the Whitman Massacre in 1847. His fourth daughter, Virginia, later became his caretaker in his later years.

7. His Legacy Lives On

Jim Bridger passed away in 1881, nearly penniless and relying on his daughter for support. However, his legacy as a mountain man lives on across the United States. Many places, especially in the West, are named after him. A replica of Fort Bridger still stands for visitors to see. You can explore Bridger-Teton National Forest in Wyoming, which includes the Bridger Wilderness. The Bridger Range, or Bridger Mountains, in Montana offers plenty of outdoor activities with many peaks to enjoy. Modern locations also honor Bridger, including the Bridger Bowl Ski Area and the Jim Bridger Power Station.

Jim Bridger was not a perfect man; he made mistakes and didn’t always act honestly. However, he had his moment of glory during America’s era of Manifest Destiny as a rugged explorer paving the way for future generations. Although his life came to an end, Jim Bridger’s legacy continues to be remembered in American history.