Sarah Emma Edmonds: Civil War Hero

Historians say that Sarah Emma Edmonds exaggerated many aspects of her wartime experiences. Still, she bravely served in the Union Army, becoming one of hundreds of women who fought in the conflict in secret

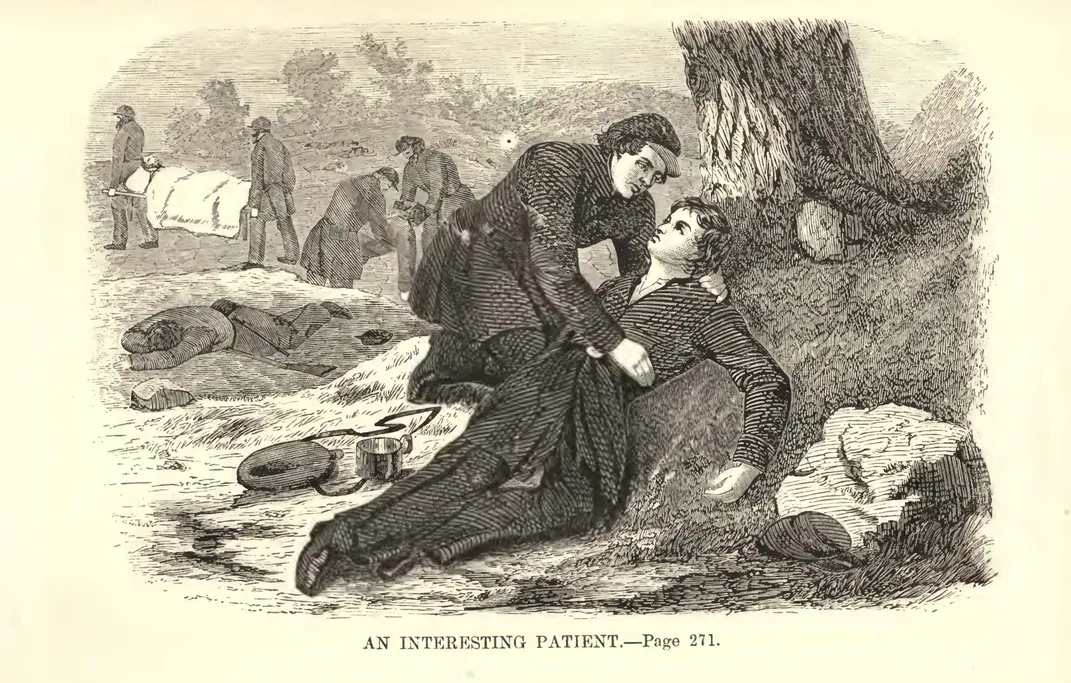

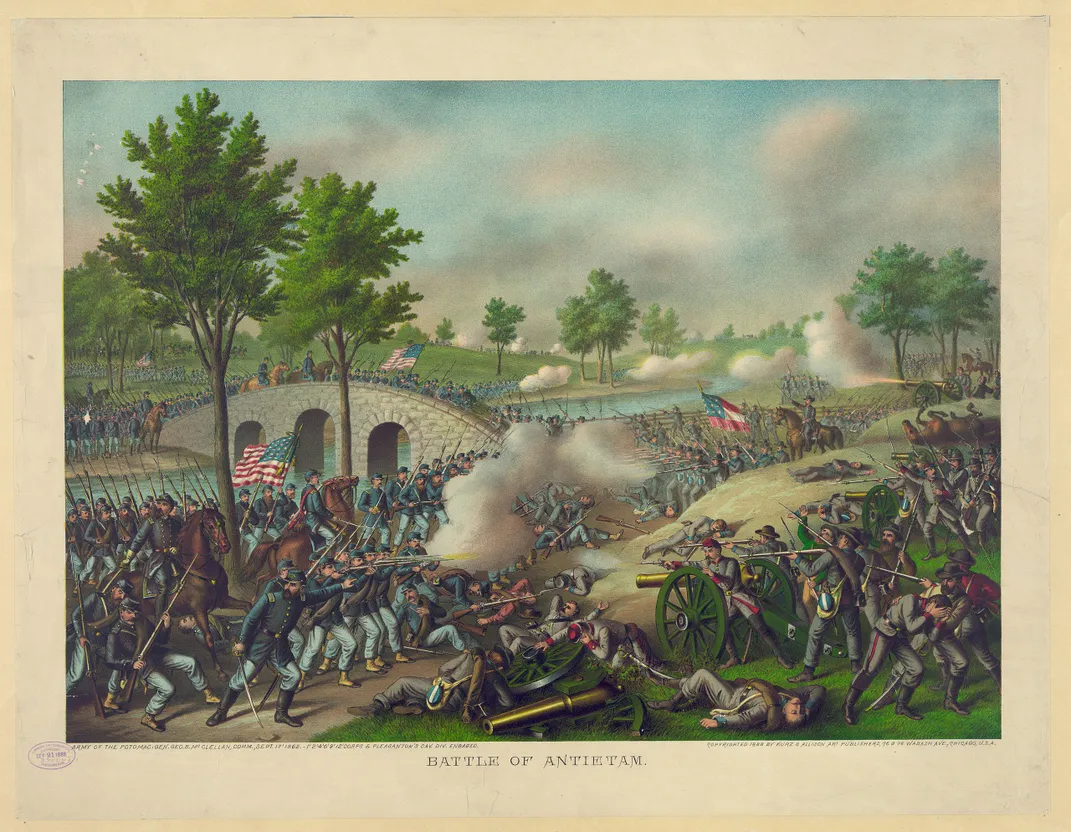

On the evening of September 17, 1862, after the Battle of Antietam, Private Franklin Thompson from the Second Michigan Infantry Regiment walked among the wounded, dying, and dead. He later recalled seeing a young soldier with a severe neck wound who was bleeding heavily. Thompson knelt down to ask if he could help.

“Yes, yes; there is something that needs to be done quickly, for I am dying,” the soldier replied.

Thompson noticed something in the wounded man’s tone and voice that made him pay closer attention to his face. The soldier motioned for Thompson to come nearer and made a deathbed confession:

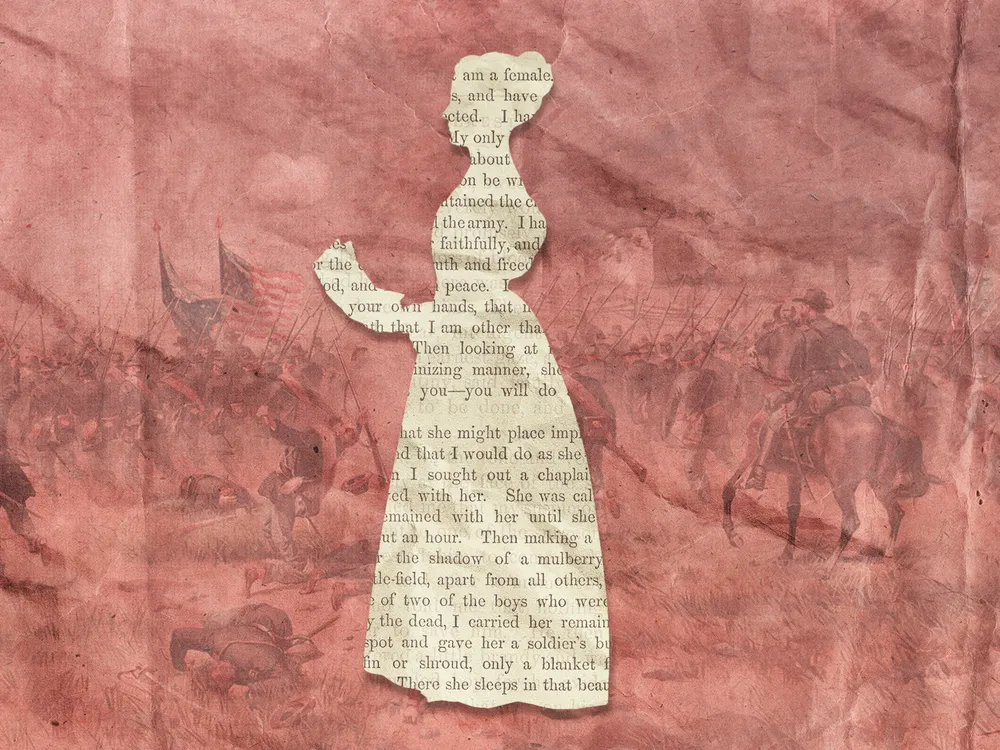

I can trust you and will tell you a secret. I am not what I seem, but am a female. I enlisted from the purest motives and have remained undiscovered and unsuspected. … I wish you to bury me with your own hands, that none may know after my death that I am other than my appearance indicates.

Thompson later said that he had done what the soldier asked. During the last hours of the bloodiest single day in American history, when over 22,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured near Sharpsburg, Maryland, the private buried the woman under the shade of a mulberry tree. Thompson had a secret of his own: he was also a woman disguised as a man.

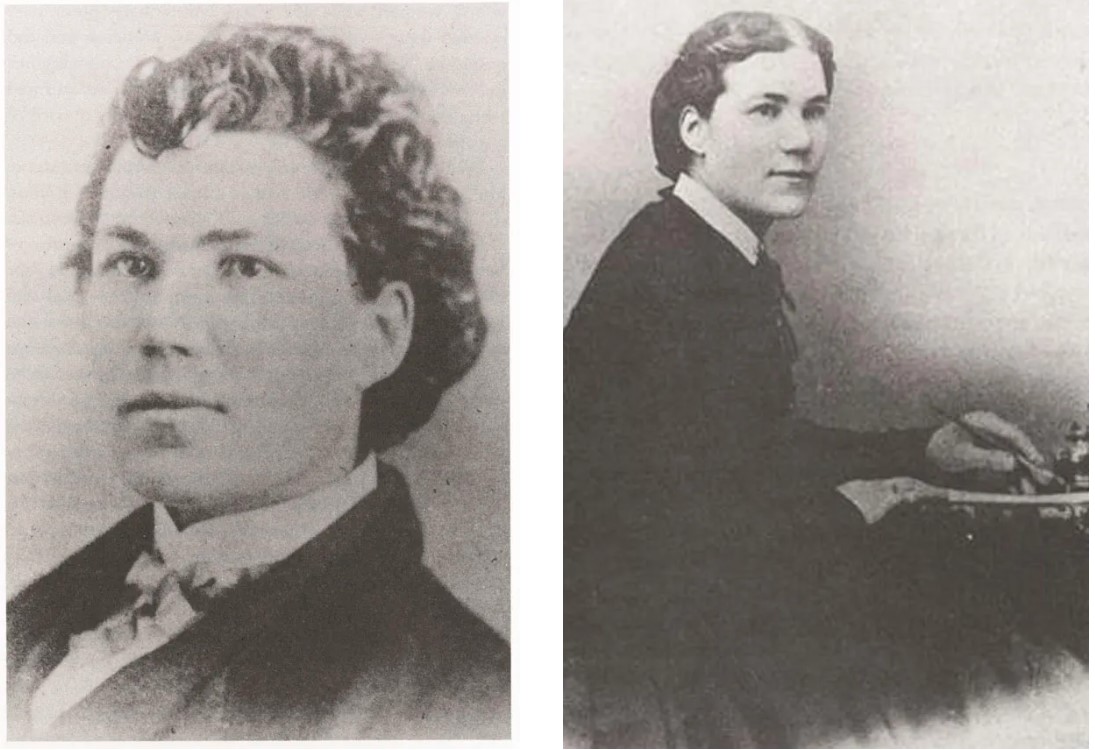

The private’s real name was Sarah Emma Edmonds, and she enlisted in the Union Army in the spring of 1861. In her memoir, Edmonds wrote that she served as both a field nurse and a spy, going undercover behind enemy lines during the Civil War. While historians debate some details of her stories—likely including her presence at the Battle of Antietam—her bravery and contributions to the war effort are widely recognized.

Edmonds was born Sarah Emma Edmondson in December 1841 in New Brunswick, Canada. Her father, a farmer who had wanted a son, treated her poorly. In 1857, she left home to escape his abuse and an arranged marriage he was forcing on her, changing her last name to Edmonds to distance herself from her family. After about a year in the Canadian town of Moncton, she feared her father would find her and decided to immigrate to the United States.

After arriving in her new home, Edmonds began disguising herself as a man to find work. She took on the name Thompson and got a job as a traveling Bible salesman based in Hartford, Connecticut.

While waiting for a train back to New England in the spring of 1861, Edmonds heard someone reading President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to fight for the Union. Just a few days earlier, on April 12, the Confederates had attacked Fort Sumter, marking the start of the Civil War.

“This announcement startled me, as I imagined the coming struggle and its terrible impact,” Edmonds wrote in her memoir. “War, civil war, with all its horrors seemed unavoidable, ready to erupt on a nation that had been so happy and prosperous. The thought of this sad situation brought tears to my eyes and sorrow to my heart.”

Edmonds is often recognized as one of the few hidden female fighters who took part in the Battle of Antietam. However, her touching story of meeting another woman soldier after the battle doesn’t align with historical records. According to troop movement reports, the Second Michigan was assigned to defend Washington, D.C., from September 3 to October 11, 1862. Interestingly, Edmonds’ company records show no information about her movements between the end of August and October 31. They simply state that she was “absent” on duty under a colonel’s orders. This raises the question: what was Edmonds doing at Antietam if she was indeed present?

Sarah Kay Bierle, an education associate at the American Battlefield Trust, suggests that Edmonds might have been delivering messages between generals or working as a nurse.

Related Post: Insane True Stories That Change How You Picture WWII

“She doesn’t provide much detail about what she was doing at Antietam; she mainly shares what she saw,” Bierle explains. “It’s hard to say for sure. According to her memoir, she was there and helped care for the wounded afterward.”

However, historians Tracey McIntire and Audrey Scanlan-Teller, who give joint presentations about women in the Civil War, are doubtful about Edmonds’ account. “Our theory is that she wasn’t actually at Antietam at all,” says McIntire, who is the director of communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. “Her story about finding another woman soldier and explaining why she enlisted seems more like a way for her to express her own reasons for joining. It’s a literary device where she uses another woman to say what she would say if she could.”

Scanlan-Teller notes that the language used by the dying female soldier closely resembles a publisher’s notice at the beginning of Edmonds’ memoir, which describes her wartime service as driven by “the purest motives and most praiseworthy patriotism.” In a 2005 biography of Edmonds, author Laura Leedy Gansler pointed out that this story was “strangely, and suspiciously, similar” to an experience of Clara Barton. After the Battle of Antietam, Barton met 16-year-old Mary Galloway, who had disguised herself as a man to follow her boyfriend into battle. Barton treated Galloway’s wounds and helped her reunite with her lover.

Whether or not Edmonds was present at Antietam, she showed great courage throughout her time in the war. A congressional report based on testimonies from her fellow soldiers stated that Edmonds participated in all the hardships and battles of her regiment. She was “never absent from duty, obeying all orders with intelligence and eagerness.”

In the spring of 1863, while in Kentucky with the Second Michigan, Edmonds became ill with a relapse of malaria, which she had caught the previous year during the Peninsula Campaign in southeastern Virginia. She requested time off but was denied. Fearing that Army doctors would discover her true identity, Edmonds decided to leave her regiment and never returned. As a result, “Thompson” was charged with desertion, which was a serious crime that could lead to death.

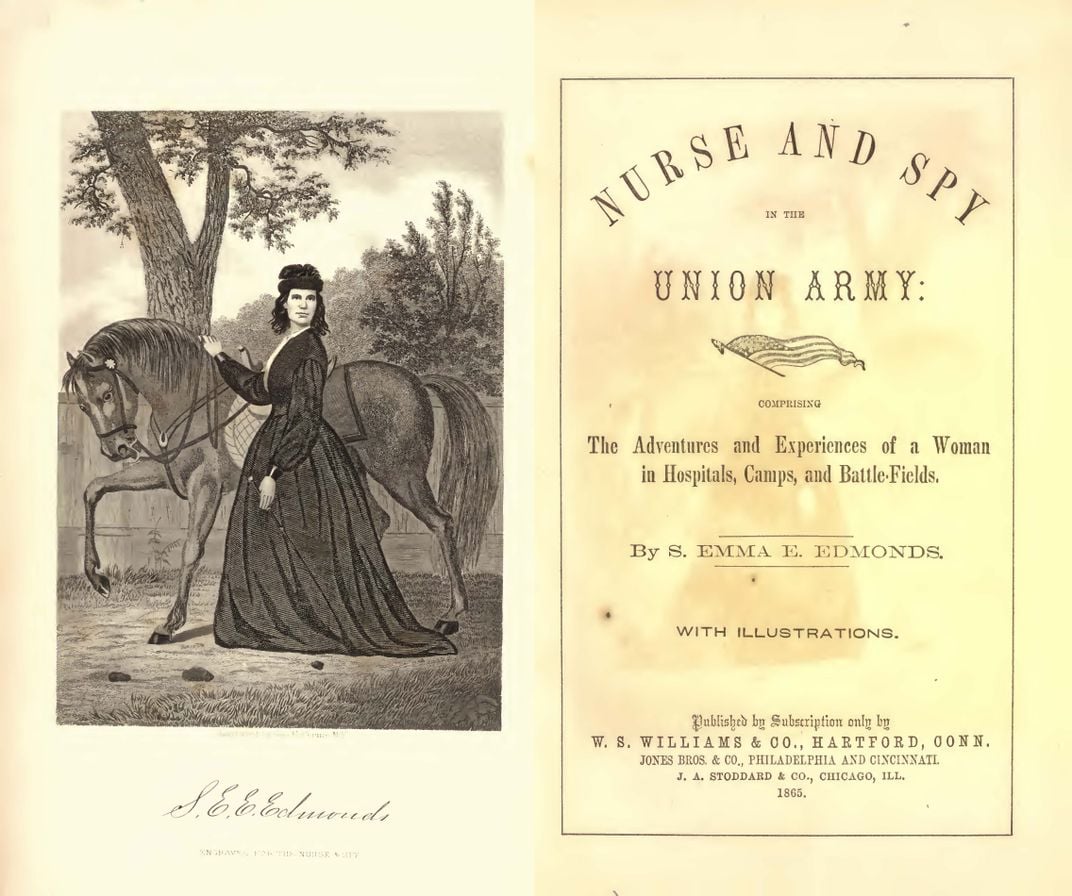

Once she recovered, Edmonds joined the United States Christian Commission as a nurse, this time without a disguise, serving from June 1863 until the war ended in April 1865. In her free time, she wrote her memoir, published as *Unsexed, or the Female Soldier* in 1864. The title did not attract many buyers, but when the book was reissued in 1865 as *Nurse and Spy in the Union Army*, it became a bestseller. Edmonds donated most of the money from her book to support soldiers’ aid groups.

“Edmonds was very vague about many personal details in her book,” says Elizabeth D. Leonard, author of *All the Daring of the Soldier: Women of the Civil War Armies.* “Her main goal was to share her experiences and make money by telling an interesting story to an eager audience. Like many Hollywood portrayals of Civil War history today, she likely took some creative liberties for her own reasons.”

Edmonds claimed that she served as a spy for the Union, pretending to be an Irish peddler named Bridget O’Shea and a Black man named Cuff. To pass as Black, she reportedly dyed her skin with silver nitrate and wore a wig. However, there are no official records of her spying activities. Leonard noted in *All the Daring* that Edmonds later admitted her autobiography was “much fictionalized,” and in a sworn statement, she denied being involved in “any secret services.”

The creative choices made by Edmonds may have stemmed from her desire to connect with her audience. “She doesn’t clearly say, ‘I enlisted as a man in the Second Michigan,’” says Scanlan-Teller. Given the gender norms and expectations of that time, the historian believes the public would likely have disapproved of such actions.

The publisher’s notice in Edmonds’ memoir seems to address potential criticisms by reminding readers that those who “object to some of her disguises” should consider the patriotism that inspired Edmonds to enlist. The notice stated, “She set aside her own clothes and wore those of the opposite sex, enduring hardships, suffering great privations, and risking her life for her adopted country in its time of need.”

Most women who secretly joined the military during the Civil War were not motivated by a desire to fight. “Researchers have found that they often enlisted and disguised themselves as men to escape abusive family situations, or they chose this path to stay close to a male family member,” Bierle explains. Patriotism and financial needs also played a role in their decision to enlist.

Women who disguised themselves as male soldiers were clever in maintaining their ruse. They cut their hair short, bound their chests, and imitated how men walked, talked, and even tied their shoes, explains Bierle. Some women, like Edmonds, managed to fight for years without being discovered. However, others, like Mary Scaberry, were discharged after just a few months when their true identities were revealed, often because they sought treatment for injuries or made mistakes while pretending to be men.

Since women served in secret during the Civil War, it’s hard to know exactly how many participated, but estimates usually range from 400 to 750. McIntire notes that at least four women fought in the Battle of Antietam, including Rebecca Peterman from the Seventh Wisconsin Infantry. There is also at least one unidentified woman buried in Antietam National Cemetery. According to a Union private’s memoir, his unit found the body of an unknown woman who had fought on the Confederate side at Antietam, and they buried her separately from the men.

Edmonds married a man named Linus Seelye in 1867, and they had three children together.

Over time, Edmonds earned the acceptance and respect of her fellow soldiers. In 1876, she attended a reunion of the Second Michigan as her true self. Her male comrades were likely surprised to learn that “Thompson” was actually a woman, but they welcomed her back. They also supported her appeal for her revoked pension, which was taken away due to desertion charges. The government finally awarded her the pension in 1884.

In 1897, Edmonds became the only female member of the Grand Army of the Republic, a veterans’ association for Civil War soldiers. She passed away at her home in La Porte, Texas, in September 1901, at the age of 56. Later that year, she was reburied with military honors in the Grand Army section of Houston’s Washington Cemetery.

You may also like:

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin: the woman who found hydrogen in the stars