Last male of his kind: The rhino that became a conservation icon

Future in the freezer!! How a species of rhinos can be saved in a test tube.

The northern white rhino is nearly extinct, with only two females left. Sadly, the last two males died a few years ago, and the remaining females are too weak to have babies. However, there is still hope. In an Italian lab, scientists are using eggs from these females and fertilizing them with sperm from the deceased males. The fertilized eggs are stored at an extremely cold temperature of -196°C. The plan is to use rhinos from a different subspecies as surrogates to carry the babies, potentially bringing the northern white rhino back from the edge of extinction.

Bringing Rhinos Back: A Glimpse of Hope in a Lab

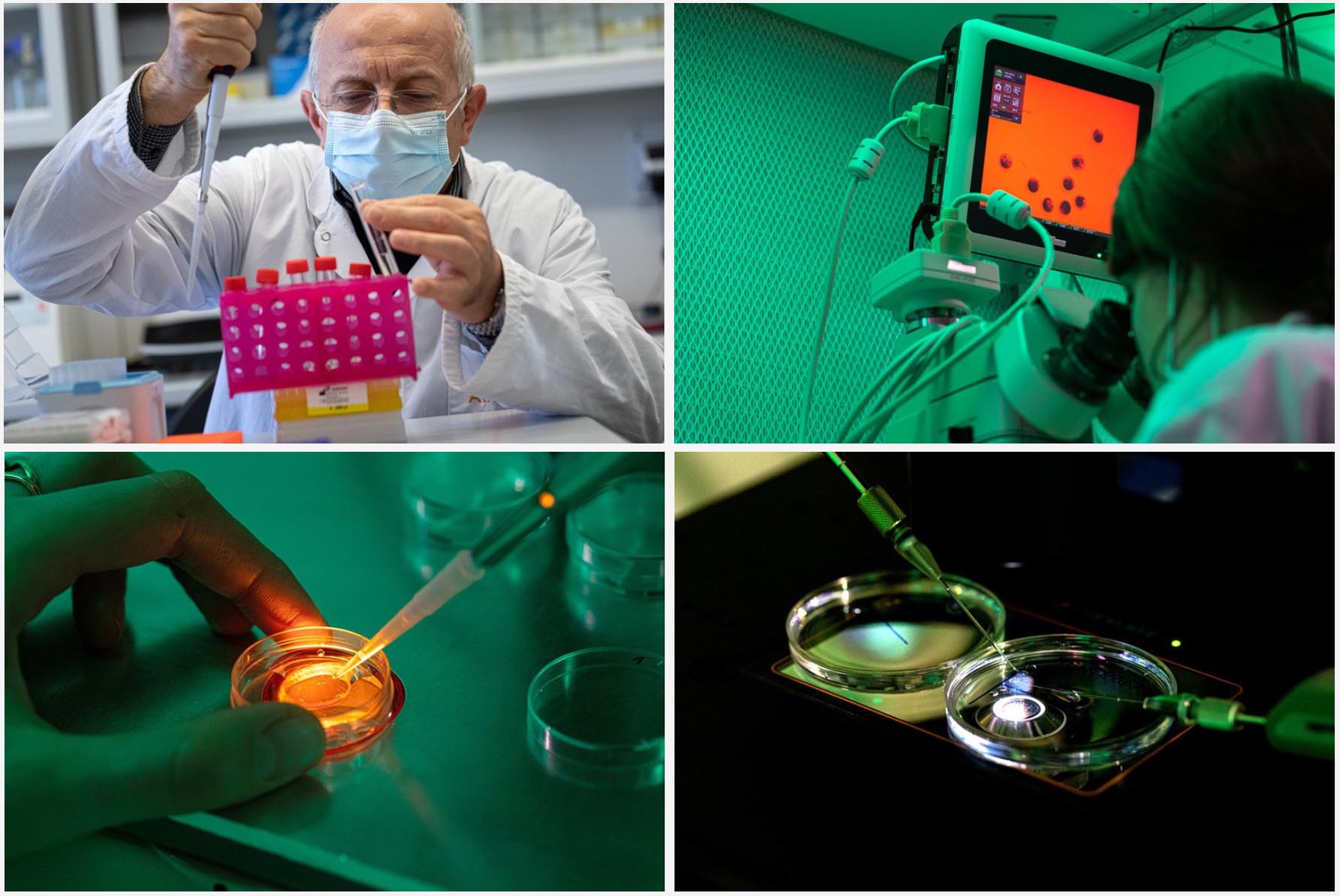

Cesare Galli carefully opened a liquid nitrogen canister and pulled out a sample labeled “Fatu NWR x Suni NWR, 9. 4. 21.” Inside were two northern white rhino embryos, created in March and April at the Avantea lab in Cremona, Italy.

So far, the lab has successfully created 14 embryos. The scientists, working with the BioRescue team, aim to use these embryos to revive the nearly extinct species. Only two female northern white rhinos remain, Fatu and Najin, but they can no longer conceive naturally.

Galli is eagerly waiting for the birth of the first northern white rhino in 22 years. “When people ask me when it will happen, I say, ‘In five years’ time.’ I’ve been saying that for a couple of years,” said Galli, founder and manager of Avantea, a biotech company specializing in advanced animal reproduction technologies.

From Horses to Rhinos: How a Lab’s Expertise is Helping Save a Species

Avantea, a company with over 20 years of experience in elite horse reproduction, was invited to join the northern white rhino project because of its outstanding reputation. Horses are the closest farm animals biologically related to rhinos, making Avantea’s expertise particularly valuable.

The lab was the first to successfully use a technique called ICSI (Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection) to artificially impregnate a mare. This method involves directly injecting a sperm cell into the egg, and it’s now one of the most common techniques used in human fertility treatments. Avantea is applying this same cutting-edge technology to help save the northern white rhino from extinction.

Adapting Horse Breeding Techniques to Save Rhinos

Avantea’s experts quickly adjusted their horse-breeding methods to create rhino embryos. Before that, Cesare Galli spent years working with Sumatran and southern white rhinos, though he couldn’t produce an embryo. In 2018, he succeeded in creating a hybrid embryo between a northern and southern white rhino.

In 2019, Avantea created 14 northern white rhino embryos, now stored at -196°C. The eggs came from 21-year-old Fatu, a female at Kenya’s Ol Pejeta Conservancy, while the sperm came from two deceased males, Suni and Angalifu. Attempts to use eggs from Fatu’s mother, 32-year-old Najin, were unsuccessful due to her age and health. After an ethical review in 2021, the BioRescue team decided to stop collecting her eggs.

Since neither Fatu nor Najin can carry a pregnancy, the embryos will be implanted in southern white rhino surrogate mothers. Thomas Hildebrandt, who leads the Reproduction Management Department at Leibniz-IZW, is optimistic this could happen soon. “We’re hoping to do the first embryo transfer in the coming months,” said Hildebrandt, who developed the embryo transfer technology and is a key figure in the project. He emphasized the need to act quickly while momentum is strong.

A Race Against Time to Save the Northern White Rhino

One female and two males aren’t enough to build a self-sustaining population,” admits Cesare Galli. “But if we can create four embryos per year, that’s sixteen in four years. With a 50% success rate, like we have with horses, we could have eight new animals. It’s not enough to repopulate Kenya, but it’s a start.

Galli emphasizes the importance of rhinos in maintaining ecosystem balance. When you eliminate a species, the whole system can fall out of balance. Rhinos are key to keeping that balance, and they’re iconic. The threat to their survival comes solely from humans, and we have a duty to make things right. Southern white rhinos faced a similar situation, but after South Africa gave them special protection, their numbers grew to over 20,000. The northern white rhinos, unfortunately, were caught in the crossfire of wars across their habitats in Uganda, Chad, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Related: A Wild Tiger Asks A Man For Help To Get Noose Off Around Its Neck

Protected but Endangered

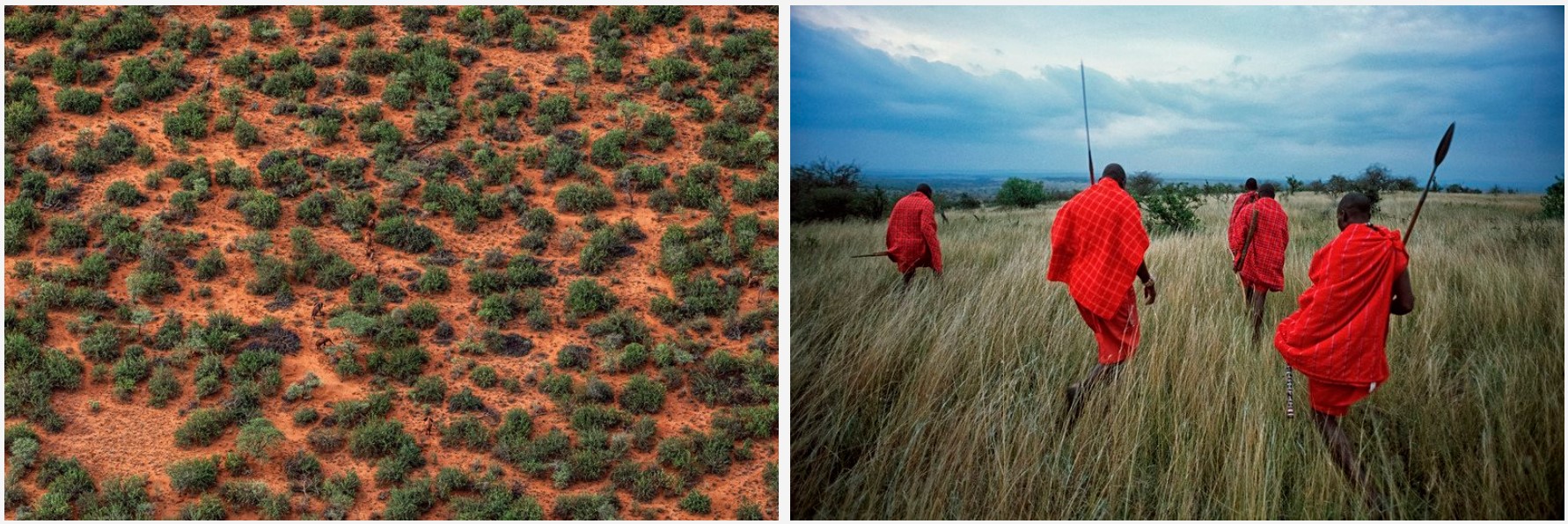

The last two northern white rhinos on Earth, Fatu and Najin, live under heavy protection at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in central Kenya. Surrounded by three electric fences and guarded by rangers, they seem unaware of the dire situation their species faces. Their lives follow a simple routine—nights spent in straw-filled pens, and days grazing in their 2.8-square-kilometer enclosure.

From six to nine in the morning, they graze, drink water when it gets too hot, and then rest. Once the weather cools, they resume grazing. They love rain, enjoy spontaneous mud baths, and often sharpen their horns on nearby trees, unaware of the critical role they play in the future of their species.

Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Nanyuki, Kenya 12. Apr. 2021

Zachary Mutai, head caregiver at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, calls Najin and Fatu “happy slaves of routine.” When asked what brings them joy, Zachary pauses before answering, “Food is very important.” During the dry season, bales of straw keep them fed, while carrots (two kilos a day) serve as their favorite treat.

Zachary’s dedication to these rhinos is clear. Najin, the older of the two, enjoys being stroked behind her ears and along her side. Fatu, however, is more unpredictable, so he maintains a respectful distance from her. Despite their size—they’re the second largest land mammals—his care for them goes beyond just keeping safe. He speaks to them softly, never raising his voice, and after spending years with them, he knows every detail of their behavior.

As we walked with Zachary, it was clear he was tuned into the natural world around him. A bird expert, he never gets bored while Najin and Fatu graze. As we followed the two rhinos, occasionally hearing them release a loud grunt, Zachary would stop, raise a finger, and point out the bird responsible for the sound. The distant roar of lions and chattering monkeys added to the atmosphere, while nearby, a group of ostriches practiced their sprints. Zachary’s keen eye can spot rhinos from over a kilometer away, a skill that comes from years of experience.

Zachary Mutai always dreamed of becoming a conservationist. “I grew up near the Masai Mara National Reserve, where we had plenty of wildlife. My father worked at Ol Pejeta when it was still a cattle ranch. When the ranch shifted to wildlife conservation, I seized the chance to get a job.” He started out maintaining electric fences but eventually became the head caregiver for the rhinos. “I’ve been doing this for over ten years now,” he shared.

A Journey of Survival

Najin and Fatu’s story began at the Dvůr Králové Safari Park in the Czech Republic, which still legally owns them. They are direct descendants of the last northern white rhino male, Sudan. Najin is his daughter, and Fatu is his granddaughter.

In 2009, Najin, Fatu, and a male named Suni were moved to Ol Pejeta in Kenya, hoping that returning to their natural habitat would spark reproduction. Unfortunately, things didn’t go as planned. Though the rhinos, including Sudan, mated, no calves were born. In 2014, Suni passed away at age 34. Then, on March 18, 2018, Sudan, the last remaining northern white rhino male, collapsed. Unable to recover, he was put to sleep the following day due to severe pain.

A Heartbreaking Loss and a Glimmer of Hope for the Northern White Rhinos

When Sudan, the last male northern white rhino, passed away in 2018, it was a devastating moment. “It felt like the whole world went dark,” Zachary Mutai, his caregiver, recalled. “All the caretakers were crying. I was fortunate to be by his side in his final moments. He was a friend to many here.”

Back in 2015, Czech veterinarians confirmed that Najin and Fatu, the last two northern white rhinos, could no longer reproduce naturally. Najin’s years in captivity had weakened her hind legs, making her unable to bear the weight of a male. Scans also revealed a large cyst on her ovary and benign tumors on her cervix and uterus. Fatu, on the other hand, was found to have degenerative issues in her womb. “Their reproductive capacity is severely diminished,” said Stephen Ngulu, head vet at Ol Pejeta, “but they’re otherwise in good health.”

Related: Discover the Adorable Aardwolf: The Little-known “Wolf” You’ll Fall in Love With

A Complex Rescue Plan

In 2015, a team of 20 scientists from around the world came together to create a rescue plan for the northern white rhinos. At the time, only Najin, Fatu, and Sudan were still alive. The only option was to try complex and costly stem-cell technologies—methods never before tested on rhinos. Even collecting eggs (oocytes) from the females was incredibly difficult, as rhino ovaries are only about the size of a human fist. The process is so taxing on the rhinos that they must be heavily sedated each time.

Despite the challenges, the entire procedure has been carefully designed to meet ethical standards. According to Stephen Ngulu, the collection of oocytes has no significant impact on Fatu’s wellbeing.

Looking to the Future

Four southern white rhino females, who have successfully reproduced before, are now at Ol Pejeta, ready to serve as surrogate mothers for northern white embryos. However, before the embryos can be implanted, scientists must conduct extensive research on the surrogates’ reproductive cycles to increase the chances of success.

A New Hope for the Northern White Rhino Project

The plan is to first implant a southern white rhino embryo, and if it’s successful, a northern white rhino embryo will be next. Although the COVID-19 pandemic caused delays, the team at Ol Pejeta remains confident that the first embryos will be implanted within this year.

“The assisted reproduction technology is already showing results—the embryos we created are alive,” says Cesare Galli. Another approach being explored involves creating reproductive cells from induced pluripotent stem cells taken from the preserved tissue of deceased northern white rhinos. Katsuhiko Hayashi from Kyushu University in Japan leads the way in this cutting-edge field.

“This is an expensive project,” admits Richard Vigne, former CEO of Ol Pejeta. “Some say it’s not worth it to save one species when thousands of others are also at risk. We disagree.” Vigne highlights that the northern white rhino project has brought significant global awareness to the broader issue of animal extinction.

“Sudan has become a global icon!” Vigne exclaims. “This was a huge win for conservation!”

From Ranch to Conservation Hub

Ol Pejeta, once a cattle ranch in colonial Kenya, was divided into fenced plots for livestock. Wildlife that wandered into the area was exterminated. But after Kenya banned wildlife hunting in 1977, animals, particularly elephants, started returning. The financial burden on ranchers led to a shift toward wildlife tourism, sparking Ol Pejeta’s transformation into the conservation hub it is today.

The Rise of Sweetwaters Game Reserve: A Rhino Success Story

In 1988, Ol Pejeta Ranch established the Sweetwaters Game Reserve, initially focusing on saving critically endangered black rhinos. This initiative aligned with the Kenya Wildlife Service’s decision to relocate all black rhinos to protected game reserves. The reserve began with just 20 black rhinos, and today that number has grown to 149, making Ol Pejeta the largest black rhino sanctuary in Eastern Africa.

Richard Vigne, who first managed the ranch and later the entire conservancy, introduced a successful business model that combined livestock ranching with conservation and tourism. “We employ about a thousand people, pay significant taxes, and help maintain ecological balance. For our local community, this is a win-win!” he said.

Impact of the Pandemic on Ol Pejeta Conservancy

The recent pandemic significantly affected the conservancy’s tourism income. “In 2019, we welcomed 115,000 visitors, but last year, that number dropped to just 30,000,” said Richard Vigne with a sigh. “And 56 percent of those visitors were locals, who spend much less. We expected tourism to generate around $12 million last year, but it only brought in $1.6 million.”

Despite these challenges, Kenya’s approach to rhino conservation has been successful. Over the past few years, the rhino population has been growing by five to seven percent annually. In 2020, for the first time in two decades, not a single rhino was shot in the country, and Ol Pejeta has maintained this record for three years.

Now, the conservancy is home to 190 rhinos. “Kenya has done an excellent job protecting elephants and rhinos,” Vigne acknowledged. “Since 2014, most of the rhinos here die of natural causes, but they can only thrive in a protected environment. Poaching is no longer our biggest concern; the main issue now is lack of space.”

The Impact of COVID-19 on Ol Pejeta Conservancy

The recent pandemic had a big impact on the conservancy’s tourism income. “In 2019, we had 115,000 visitors, but last year, only 30,000 came,” Richard Vigne said sadly. “And 56 percent of those were locals who spend much less. We expected tourism to generate about $12 million last year, but it only brought in $1.6 million.”

Despite these setbacks, Kenya’s approach to rhino conservation has been successful. In recent years, the rhino population has been growing by five to seven percent each year. In 2020, there were no rhinos shot in the country for the first time in two decades, and Ol Pejeta has maintained this for three years.

Currently, the conservancy is home to 190 rhinos. “Kenya has done an excellent job protecting elephants and rhinos,” Vigne noted. “This has especially been true since 2014. Most of the rhinos here die of natural causes, but they can only thrive in a protected environment. Our biggest concern is no longer poaching; it’s a lack of space.”

Ol Pejeta’s Black Rhino Conservation Efforts

Ol Pejeta Conservancy has exceeded its capacity for black rhinos, prompting management to buy an additional 20,000 acres of land from the local community.

The success of rhino conservation in Kenya is mainly due to the wildlife-hunting ban established in the 1970s and a 2013 law that imposes life imprisonment or a fine of 20 million Kenyan shillings for anyone caught with a rhino horn or elephant tusk. There is strong political support for rhino preservation, and public awareness has increased.

However, Kenya is just a small part of Africa, which still faces serious poaching issues, often driven by organized crime groups from Asia. In 2015, poaching claimed the lives of 1,324 rhinos, but that number dropped to 435 in 2020, with most of the deaths (394) occurring in South Africa. South Africa has the largest rhino population in the world and allows trophy hunting of rhinos and elephants, with private reserves breeding these animals for hunting.

Rhino Poaching: A Persistent Threat

Despite the positive news about rhino recovery, poaching is still a reality. Richard Vigne shared that Ol Pejeta faces at least one poaching attempt every month, with three criminal gangs active in the area. The dark history of poaching is reflected in Ol Pejeta’s rhino cemetery, where many rhinos killed since 2004 are laid to rest.

Out of the 22 rhinos buried there, only two, Sudan and Suni, died from natural causes. One of the tragic cases is a female black rhino named Ishirini, whose gravestone reads: “Born May 17, 1996. Died February 22, 2016. Probably killed by a poison dart. A security team found her in great pain, with her horns already cut off. She was twelve months pregnant.”

Zachary Mutai, the head caregiver at Ol Pejeta, held up a small piece of rhino horn from Najin’s smaller horn and said, “They’re hunting them for their horns, which are made of keratin, the same substance as our nails and hair!”

In places like China and Vietnam, rhino horns are believed to be a miracle cure for everything from hangovers to cancer. This belief has made rhino horns incredibly valuable, with one kilogram fetching $65,000 on the Asian black market.

During our visit, we saw the youngest southern white rhino at Ol Pejeta, born just this March. Still without a horn, this playful little calf was energetically bumping into its parents as they grazed. His mother eventually nudged him away, sending him flying a meter to the side. But that didn’t stop him—he got right back up and continued his playful antics.