The Acacus Mountains’ final cry: Prehistoric civilisation dating back 14,000 years on the verge of extinction

The Acacus Mountains, also called Tadrart Akakus by the locals, sit in the Fezzan area of southwest Libya, right in the Sahara Desert.

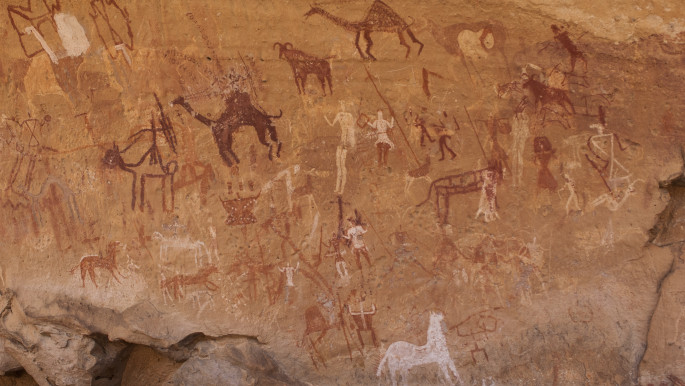

These mountains are famous for their many paintings and carvings found on cave walls, mountainsides, and rocks. These artworks show animals like giraffes, elephants, and ostriches, as well as scenes from ancient human life, like people and horses.

“Illegal hunting and oil companies are among the biggest challenges facing the Akakus Mountains. For extended periods, the oil companies operating in the southern Libyan desert have disregarded environmental preservation standards and the safety of the local population”

Throughout history, the walls of Acacus have been respected and admired by many generations. But in the latter part of the twentieth century, incidents of destruction and vandalism started happening, especially as more tourists visited the area.

In 2008, a driver from a tourism company got into a fight with an Italian woman who owned the company. In revenge, he came back and spray-painted 125 panels.

Archaeologists suggested leaving the paint alone and letting it fade naturally over time due to weathering, even though it might take a while to completely disappear.

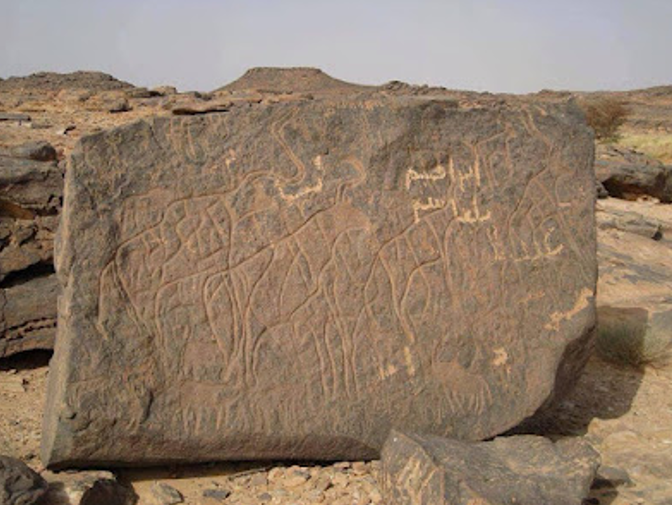

Furthermore, some vandals tried to make a permanent mark for themselves by carving their names onto panels that are 5,000 years old, thinking that this would ensure they’d be remembered by future generations, just like we remember ancient civilizations.

The protection of antiquities and the Libyan law

Messing with ancient artifacts is against the law. According to Libyan Law No.10 of 1983 for the Protection of Antiquities, doing anything that damages or destroys ancient artifacts or historical places is a crime. People who do this can face fines or even go to jail.

At the same time, some people in the tourism industry are pushing for tougher laws and stricter punishments for those who damage ancient artifacts, hoping it will stop others from doing the same.

However, the current law isn’t being enforced very seriously. Vandals and people who damage ancient things often don’t get punished.

There’s also a problem with who’s in charge. The Ministry of Tourism and the Ministry of Culture both have a role in this, which makes things more complicated and harder to fix.

He added, “Exploratory trips have been stopped for more than ten years, and there aren’t enough studies, research, or centers to help tourism, especially in the south and specifically in this area. There are still many artifacts buried under the sand. It’s the government’s job to keep things safe and promote international tourism. If they really want to help tourism, security won’t be such a big problem if everyone works together.”

Khaled Abdul Salam, a teacher from Al-‘Awaynat, also blamed the authorities and said they need to give the tourist police better equipment and training, especially since the area is like an outdoor museum in the middle of the desert and needs more security.

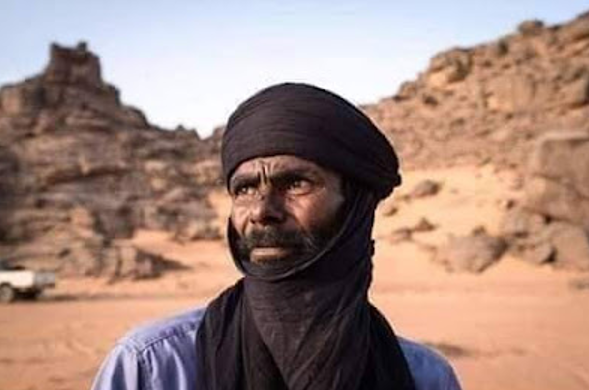

He and his children live near the Avaazagar arch in the Libyan desert. Their job is to stop thieves and vandals from damaging the mountains.

They see this place, along with the local Tuareg people, as their ancestors’ homeland. They worry that if they leave, others might come and harm the valuable ancient carvings.

They believe that by staying close to these historic engravings, they’re keeping a precious treasure safe. Andalan may have left, but his children stay behind to watch over the mountains.

Wrapped in animal skin, the mummy was found by an Italian archaeologist in 1958. It’s been preserved for about 5,500 years, even before the ancient Egyptians began mummifying people.

Today, you can see the mummy in the National Museum in Tripoli, the capital city.

The Arab world’s foundational role in human civilisation has meant the region is awash with protected sites, but a lot of these sites are now at risk of collapse 👇 https://t.co/pejBQ4mEsQ

— The New Arab (@The_NewArab) January 15, 2023

The Akakus Mountains face big problems like illegal hunting and actions by oil companies. For a long time, these companies in the southern Libyan desert haven’t followed rules to protect the environment or keep locals safe. They’ve left a lot of damage behind without helping the people who live there.

The damage to the environment, changes to the landscape, and the rich history of the area continue without being stopped. Another big problem is illegal hunting by people who only care about making money.

These mountains cover a big area with lots of different animals, including rare ones like Barbary sheep and deer that have lived there for thousands of years. But now, these animals are in danger of dying out because hunters shoot them, hurting the caves and mountains too.

Related Post: Ötzi the Iceman: The famous frozen mummy

UNESCO added the Akakus Mountains to its World Heritage List because it saw how special they are. But it also put them on the list of places in danger.

In their report from 2021, UNESCO said this was because of things like deliberate damage, illegal activities, and war.

Even though this is happening, the mountains don’t get enough attention from the people who should be taking care of them. Meanwhile, the locals are doing their best to protect them and are upset that no one else seems to be doing anything.

Khaled Kanu, who’s 41 and lives in Ghat, told The New Arab that a historic place like this needs real solutions, not just reports.

He wondered why UNESCO lets bad people hurt a historic place like this and said UNESCO should do its job, especially since Libya is in such a mess.

“The south of Libya is full of old sites from before history, like Amazigh rock art, Akakus, and Jarma. But these places are being damaged by vandals and destroyers. They need someone to step in and protect them.”

Samira Elsaidi is a journalist who’s worked for different news outlets.