Russian ship played classical music to rescue entrapped belugas

The Moskva was the biggest and strongest icebreaker that wasn’t nuclear when it was built. In 1985, it made news by using classical music to guide about 2000 trapped beluga whales back to open water. Yep, classical music!

What is an icebreaker?

An icebreaker is a special type of ship designed to sail through thick ice, especially in places like the Arctic where other ships can’t go. They push through the ice to make a path for other ships. Usually, they don’t tip or lean much when breaking the ice. If the ice is really thick, they can even drive right onto it to break it apart. Icebreakers were first used in expeditions to explore the North and South Poles, and today they’re still used to clear icy routes for ships and for research in the polar regions.

Moskva, a fierce Russian ship

After getting three icebreakers between 1954 and 1956, the Soviet commerce minister wanted bigger, stronger ships. So, they asked a Finnish company called Wärtsilä in Finland to build them. One of these ships was called Moskva, named after the capital of the Soviet Union, Moscow.

Moskva was designed in 1956 and had one of the most powerful diesel-electric engines ever put on a ship at that time. It was finished in 1960 and worked until 1992 when it was taken apart and sold for parts. It was huge, weighing over 13,000 tonnes and stretching 122 meters (400 feet) long. Moskva helped hundreds of ships on the North Sea trade route by breaking the ice ahead of them.

“Operation Beluga”

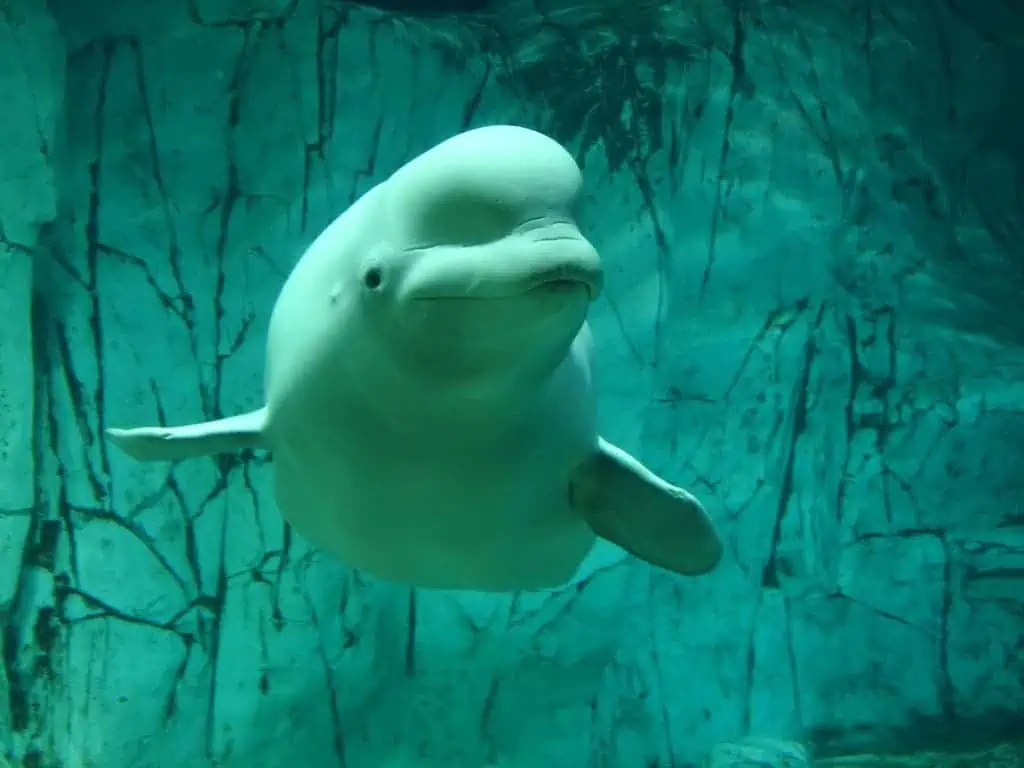

In December 1984, a hunter saw a big group of beluga whales in the icy waters near the Chukchi Peninsula. At first, the hunter and his group were glad because belugas are good to eat. But they realized there was a problem. The weather had made a thick layer of ice, about 4 meters deep, and it trapped the whales. The whales couldn’t swim through such a long stretch of ice in one breath, so they were stuck in small areas where they could come up to breathe. They needed something to break the ice and set them free.

When people found out about the trapped whales, they rushed to help. They fed them frozen fish and dug through the ice to give them space to breathe. But the winter in North-Eastern Russia is really tough, and the whales wouldn’t survive for long under the thick ice.

In early February 1985, Russia asked the Moskva to help free the trapped beluga whales by breaking through the thick ice. The ship rushed to the scene, knowing time was running out for the whales. When it arrived, the ice was so thick that the captain almost gave up. But as more whales started to die, the Moskva decided to push through the ice. Meanwhile, helicopters dropped fish near the whales’ breathing holes to keep them fed while the ship worked to make a path for them to escape.

After a few days, the Moskva and its crew got close to the whales. But the belugas were scared of the big ship and its propellers. Since nobody could talk to them in their language, the Moskva made bigger holes in the ice for the whales to swim, eat, and rest. But the whales didn’t want to follow the ship to the open ocean. What happened next is hard to believe…

Music is the universal language

Someone on the ship remembered that sea animals like music. They decided to play music from the top deck. They tried different types, like pop and classical. After a few tries, they found that the belugas responded to classical music. They began to come closer to the icebreaker.

Using classical music, the Moskva guided the group of whales back to the open sea. Captain Kovalenko told headquarters over the radio: “Here’s our plan: We move forward, then backward, breaking the ice to create a path, and then we wait. We do this over and over. Eventually, the belugas start to figure out what we’re doing and follow us. That’s how we progress, bit by bit.” The whole operation lasted for weeks, but by the end of February 1985, about 2000 whales made it back to the ocean. Whether the whales enjoyed the classical tunes remains a mystery.

Operation beluga cost Russia about $80,000 (around $200K today).