The Amazing Dinosaur Found (Accidentally) by Miners in Canada

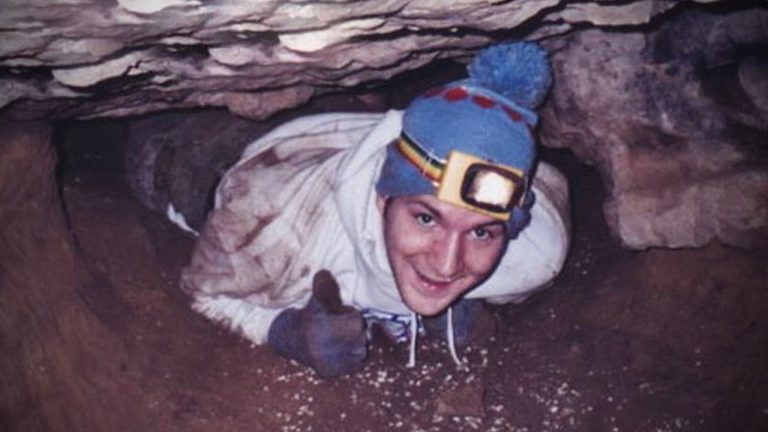

On March 21, 2011, in the afternoon, a heavy-equipment operator named Shawn Funk was working at the Millennium Mine, a big pit about 17 miles north of Fort McMurray, Alberta. This mine is run by the energy company Suncor. Funk was operating his huge excavator, digging down through layers of sand containing bitumen—a kind of thick oil made from ancient marine plants and animals that lived over 110 million years ago. He usually only saw ancient plant life in his work. Over 12 years of digging, he had found fossilized wood and sometimes petrified tree stumps, but he had never found the remains of an animal, let alone a dinosaur.

Around 1:30 in the afternoon, Funk’s excavator bucket hit something harder than the usual rock. Strange-colored lumps spilled out, rolling down onto the ground. Funk and his supervisor, Mike Gratton, quickly became curious about these walnut-brown rocks. Were they pieces of fossilized wood, or perhaps ribs? Then, they turned over one of the lumps and found a strange pattern: rows of sandy-brown disks, each surrounded by gunmetal-gray stone.

“Right away, Mike said, ‘We need to get this checked out,'” Funk recalled in a 2011 interview. “It was definitely unlike anything we had ever seen before.”

Almost six years later, I find myself at the fossil preparation lab in the Royal Tyrrell Museum, located in the windy badlands of Alberta. The huge warehouse is filled with the sounds of ventilation and technicians using needle-tipped tools to carefully remove rock from bone. However, my attention is drawn to a massive 2,500-pound chunk of stone in the corner.

At first glance, the gray blocks assembled there resemble a nine-foot-long dinosaur sculpture. Its neck and back are covered in a bony armor, and there are gray circles marking individual scales. The neck gracefully bends to the left, as if reaching for some tasty plant. But this isn’t a sculpture—it’s a real dinosaur, turned into stone from its snout to its hips.

The more I stare at it, the more incredible it seems. Fossilized pieces of skin still cover the bumpy armor plates on the animal’s skull. Its right front foot is lying next to it, with its five toes spread out. I can even see the scales on its sole. Caleb Brown, a researcher at the museum, smiles as he sees my amazement. “We don’t just have a skeleton,” he explains later. “We have a dinosaur as it would have been.”

For paleontologists, the high level of fossilization of this dinosaur—caused by its quick burial under the sea—is extremely rare, like winning the lottery. Normally, only the bones and teeth are preserved, and it’s very uncommon for minerals to replace soft tissues before they decay. Plus, there’s no guarantee that a fossil will keep its original shape. For example, feathered dinosaurs found in China were squashed flat, and North America’s “mummified” duck-billed dinosaurs, some of the most complete ever found, look shriveled and dried out.

Paleobiologist Jakob Vinther, an expert on animal colors from the University of Bristol in the UK, has examined some of the world’s best fossils for signs of the pigment melanin. But even after four days of delicate work on this one—carefully scraping off tiny samples smaller than grated Parmesan cheese—even he is amazed. The dinosaur is so well preserved that it “might have been walking around a couple of weeks ago,” Vinther says. “I’ve never seen anything like this.”

A poster for the movie Night at the Museum hangs on the wall behind Vinther. It shows a dinosaur skeleton coming out of the shadows, brought back to life by magic.

The incredible fossil is a new species (and genus) of nodosaur, a type of armored dinosaur often overlooked compared to its more famous relatives in the Ankylosauridae subgroup. Unlike ankylosaurs, nodosaurs didn’t have tail clubs, but they did have spiky armor to defend against predators. Between 110 and 112 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period, this 18-foot-long, nearly 3,000-pound giant roamed the land like a rhinoceros, a grumpy plant-eater that mostly kept to itself. And if something did try to attack, like the fearsome Acrocanthosaurus, the nodosaur had a clever defense: two 20-inch-long spikes sticking out of its shoulders like a pair of bull’s horns.

The western Canada that this dinosaur lived in was a whole different world from the cold, windy plains I saw last autumn. Back in the nodosaur’s time, that area was more like today’s South Florida, with warm, humid winds blowing through forests of conifer trees and meadows filled with ferns. It’s even possible that the nodosaur could see an ocean. During the early Cretaceous period, rising waters created an inland seaway that covered much of what’s now Alberta. Its western shore touched eastern British Columbia, where the nodosaur might have roamed. Nowadays, those old seabeds are hidden under forests and fields of wheat.

One unfortunate day, this land-loving animal ended up dead in a river, possibly washed in by a flood. Its body floated downstream, kept afloat by gases produced by bacteria inside its body. Eventually, it washed out into the seaway. Winds blew it eastward, and after about a week floating, its swollen body burst. It sank to the ocean floor, back-first, stirring up muddy sediment that buried it. Minerals seeped into its skin and armor, preserving its shape as layers of rock piled on top of it over millions of years.

The creature’s preservation depended on each step of this unusual chain of events. If it had floated a bit farther on that ancient sea, it would have fossilized outside of Suncor’s property and remained buried. Instead, Funk stumbled upon the oldest dinosaur ever found in Alberta, preserved in stone as if it had looked at Medusa.

“That was a really exciting discovery,” says Victoria Arbour, a paleontologist specializing in armored dinosaurs at Canada’s Royal Ontario Museum. Arbour has seen the fossil during its preparation stages but isn’t involved in its study. “It represents such a different environment from today and such a different time, and it’s very well preserved.” (Arbour has started studying a similarly well-preserved ankylosaur found in Montana in 2014, much of which is still hidden inside a 35,000-pound block of stone. On May 10, Arbour and her colleague David Evans published a description of the Montana ankylosaur, naming it Zuul crurivastator—”Zuul, destroyer of shins”—after the monster in the movie Ghostbusters.)

The Canadian specimen is truly remarkable, in more than one way. As this article was being prepared, museum staff were still working on the scientific description of the creature and hadn’t decided on a common name yet. (They jokingly considered “Mrs. Prickley,” a character from a Canadian comedy show, but it didn’t catch on.) However, the fossil is already offering new insights into the structure of nodosaurs’ armor. Usually, reconstructing armor involves a lot of guesswork because the bony plates, called osteoderms, tend to scatter early in the decaying process. But not with this nodosaur—its osteoderms stayed in place, along with traces of the scales in between.

What’s more, many of the osteoderms still have sheaths made of keratin, the same material as human fingernails. This lets paleontologists see exactly how these sheaths affected the size and shape of the armor. “I’ve been calling this one the Rosetta stone for armor,” says Donald Henderson, curator of dinosaurs at the Royal Tyrrell Museum.

However, getting this Rosetta stone out of its rocky tomb was no easy feat.

Once news of the discovery spread at Suncor, the company quickly informed the Royal Tyrrell Museum. Henderson and Darren Tanke, a skilled technician at the museum, rushed to Fort McMurray on a Suncor jet. Suncor workers and museum staff worked tirelessly in 12-hour shifts, surrounded by dust and diesel fumes, chipping away at the rock.

They finally reduced it to a 15,000-pound rock containing the dinosaur, ready to be lifted out of the pit. But disaster struck on camera: as it was being lifted, the rock broke apart, splitting the dinosaur into several pieces. The fossil’s partially mineralized, cake-like interior couldn’t support its own weight.

Tanke spent the night coming up with a plan to save the fossil. The next morning, Suncor workers wrapped the fragments in plaster of Paris, while Tanke and Henderson searched for anything to stabilize the fossil during the long drive to the museum. They used plaster-soaked burlap rolled up like logs instead of timber.

The makeshift plan worked. Some 420 miles later, the team arrived at the Royal Tyrrell Museum’s preparation lab, where fossil preparator Mark Mitchell took over. Mitchell’s work on the nodosaur demanded precision: for over 7,000 hours in the past five years, Mitchell carefully exposed the fossil’s skin and bone. It’s a painstaking process, akin to freeing compressed talcum powder from concrete. “You almost have to fight for every millimeter,” he says.

Mitchell’s struggle is almost done, but it will take years, maybe even decades, to fully understand the fossil he’s revealing. For instance, its skeleton is mostly hidden under its skin and armor. In a way, it’s too well preserved—getting to the dinosaur’s bones would mean destroying its outer layers. Despite CT scans funded by the National Geographic Society, the rock remains stubbornly opaque, revealing little.

For Vinther, the most groundbreaking aspects of the nodosaur fossil might be at its tiniest scale: microscopic traces of its original color. If he can reconstruct how it looked, he could uncover how the dinosaur moved around and used its strong armor.

“This armor clearly offered protection, but those big horns on its front would have been like a big advertisement,” he explains. This display might have helped attract mates or scare off rivals—and might have stood out against a background of red. Chemical tests of the dinosaur’s skin suggest the presence of reddish pigments, contrasting with the horns’ much lighter color.

In May, the Royal Tyrrell Museum will unveil the nodosaur as the main attraction of a new exhibit featuring fossils found in Alberta’s industrial areas. Now, the public is marveling at what has amazed scientists for the past six years: a visitor from Canada’s distant past, discovered in a barren landscape by a man with an excavator.