This Cave Was Sealed With A Man Trapped Inside!

The day before Thanksgiving in 2009, I was asked to help with the Nutty Putty Cave rescue of John Edward Jones. I ended up being the last person to see him alive, though he was mostly unconscious by the time I arrived. Since then, I’ve received many questions from reporters and curious people, and recently, those requests have increased due to some viral videos. This is my way of sharing what I know to help answer those questions.

The day after the rescue attempts ended, I wrote a detailed account of the experience while it was still fresh in my mind. Keep in mind that this is just one perspective, as I arrived toward the end of the rescue. For a fuller view of the event, I recommend reading Lindsay Whitehurst’s two-part article in the *Salt Lake Tribune*.

Please note that this report includes descriptions of John Jones’s condition and passing that might be upsetting to some readers. Out of respect for John and his family, I’ve kept these descriptions as general as possible while explaining the challenges we faced.

Nutty Putty Rescue Report

Written for SAR on November 25, 2009

Around 9 or 10 AM, I received a call from Spencer Christian and Rodney Mulder about an ongoing rescue at Nutty Putty Cave. They asked if I could assist, but after some questions, I learned there were already enough people on site. I told them I could come if the rescue went on for a while and they really needed more help.

About five hours later, Spencer called back, saying people were getting exhausted and they specifically needed smaller cavers. So, I left work around 4 PM, quickly grabbed my caving gear from home, and headed to Nutty Putty, arriving by 6 PM. By 6:30 PM, I was assigned to the next group entering the cave.

When I got to the main passage near the Birth Canal, I saw teams working on the 4-to-1 haul system. I helped for a few minutes, but it soon became clear the system wasn’t effective, and the team near John Jones needed a break. As they exited, I spoke with Andy Armstrong, who said John was fading fast, drifting in and out of consciousness, and describing visions of angels and demons.

Once they were out, it was decided I would go in first to assess John’s condition and consider any ideas for freeing him, followed by Debbie, who had spent time with him earlier and thought he’d feel more comfortable with her.

I went in first. Just before reaching John’s position, there’s an incredibly tight crawl space about 18 inches wide and 8-10 inches high, with a sharp 90-120 degree turn. You have to enter feet first, carefully maneuvering without being able to see your footing until you’re past the narrowest part. As I inched my way in, my feet touched something soft, which I quickly realized was John’s feet. I lifted my feet immediately and shifted into a horizontal position alongside him.

John’s feet were about six feet past the tight spot, so I was able to move to the side of him down the 4-foot-wide crack. Once stable, I introduced myself and asked how he was doing, but there was no response. I shifted slightly, tapped his leg, and heard him breathing—a heavy, gurgling sound like fluid was filling his lungs. His feet moved, as if he were trying to shift himself out of the crack, but then his movement became frantic for a moment before he stopped, appearing to slip into unconsciousness. I kept tapping his leg and hip, hoping for a response, but he didn’t react.

I took a few minutes to study the passage, John’s position, and the rescue rig to figure out a way to get him out. It looked bleak. The setup could only lift him a foot or two because the webbing was anchored at his knees, and after that, his feet would hit the ceiling. Even if he were lifted that far, the tight space would prevent him from being turned to a horizontal position unless he did it himself, but he was now unconscious. And even if we got him horizontal, he’d still need to maneuver through the most challenging parts of the passage.

Getting an unconscious person weighing 210 pounds through that tight space seemed almost impossible. Even for me, at 125 pounds, it was tough to get through, requiring me to contort my body to slip out of the bend. The only other option I saw was to widen the crack using a jackhammer, removing some of the tighter spots. This approach would likely result in significant cuts and broken bones for John, but given the circumstances, it seemed like the best available option.

After I climbed out and Debbie took my place, there was a request to bring a radio down to John so his family could speak to him. His father, mother, and wife spoke to him, expressing their love, prayers, and blessings. His wife shared a feeling of peace, saying everything would be okay. She talked to him for about 5 to 10 minutes before I explained that we needed to get back to the rescue efforts.

I then crawled out so Debbie could squeeze past to assess the situation, but her legs cramped up in the tight space, preventing her from going further. That’s when I decided to try using the jackhammer. Once it arrived, I carried it down to John’s location. The tool was much heavier than expected, and holding it up while wedging myself into the crack took all my strength. Due to the confined space, I struggled to get a good angle on the rock, managing only three tries on a small lip near John’s foot. Unfortunately, the angle forced the hammer to sink into the sand beside the rock. Adjusting my position didn’t help, as the jackhammer’s 3 to 4-foot length left little room to maneuver in the 2.5-foot space. Holding it at such an awkward angle quickly wore me out.

I asked for a smaller tool, but none were available, and even if there had been, a small hammer drill might not have been effective against the solid limestone. So we returned to the Birth Canal for a quick discussion about our next steps.

At this point, there were issues with the drills, and our only option was to use the compressed air hammer. It took about an hour to get the hose down for it. While we waited, we decided it might be best to start widening the passage from the top down, working toward John. When the drill arrived, Debbie, Max, and I spent about an hour and a half chipping away at the passage a few feet above the tight spot, around 7 to 9 feet from John. Softer rock came apart fairly easily, but harder formations took tremendous effort. The tight space made it hard to hit the rock at the right angle, causing the drill to cut into the floor instead of chipping off the knob.

After an hour and a half of work, we had only managed to remove an 18” x 4” section of rock on the ceiling and floor at the wider part of the passage. Beyond that point, the cave grew even narrower, giving only 3 to 6 inches of space above if you lay down and weighed about 125 pounds—not ideal for holding a jackhammer or finding the best angle. If we continued using the current tools or even switched to micro-blasters, I estimated it would take 3 to 7 days to reach John. So, we regrouped again to discuss the next steps.

By now, it was nearing midnight, and we were asked to check John’s vitals. A smaller paramedic was sent in to see if he could reach John. If he couldn’t, he showed me how to use the stethoscope and thermometer and where to check for a pulse. At 11:30 PM, we left the team by the Birth Canal and ventured down the passage. I went in first to check, in case the paramedic couldn’t fit.

I tried the stethoscope, positioning it about 3 inches up and to the right of his navel, but I didn’t hear a clear heartbeat—just some fluttering sounds, likely from me shaking while steadying myself. I then reached as far as I could up his torso to feel for breathing. It was hard to tell, but I didn’t feel anything. His chest, pressed against the rock, felt warmer and sweaty, but the rest of his body felt as cold as the cave walls. I removed his shoe and checked his temperature, but the thermometer showed nothing, meaning it was below the measurable range. I also noticed his feet and legs were much stiffer than before, with limited movement.

I reported my findings, then crawled out to let the paramedic try to reach him. He managed to get to John’s feet and confirmed that he had passed. John Edward Jones was pronounced dead at 11:52 PM.

Afterward, we decided to head topside for a debrief and to discuss the next steps. Before leaving, the paramedic and I returned to take photos of the passage and John’s position.

With John’s passing, retrieving his body presented an even greater challenge. His stiffening form couldn’t make it through the tight bend just above his feet without major modifications to the passage—work that could take days or weeks with a hammer drill, or possibly a bit less time with micro-blasters. Any swelling would make it almost impossible to remove him from the narrow crack until it subsided. The only way to attach a rope was by his feet.

As days went by, recovery would require hazmat suits and masks to manage health risks, but this would severely overheat the team. Even without protective suits, a person in the cave would start sweating within 10-15 minutes and need a break after 30-60 minutes. In hazmat gear, they’d likely last only 5-10 minutes. Mobility would also be greatly reduced, making the recovery attempt look increasingly difficult.

Commentary

- The 4 to 1 haul didn’t work because there were so many twists and turns in the cave between where there was room for a group to stand and haul and John’s position that the friction, even with pulleys in place was enough to render the haul system ineffective.

- This was the moment he passed away.

- Ultimately it was decided it would be too risky to rescuers to attempt to remove the body, and to this day Nutty Putty Cave is the final resting place of John Jones.

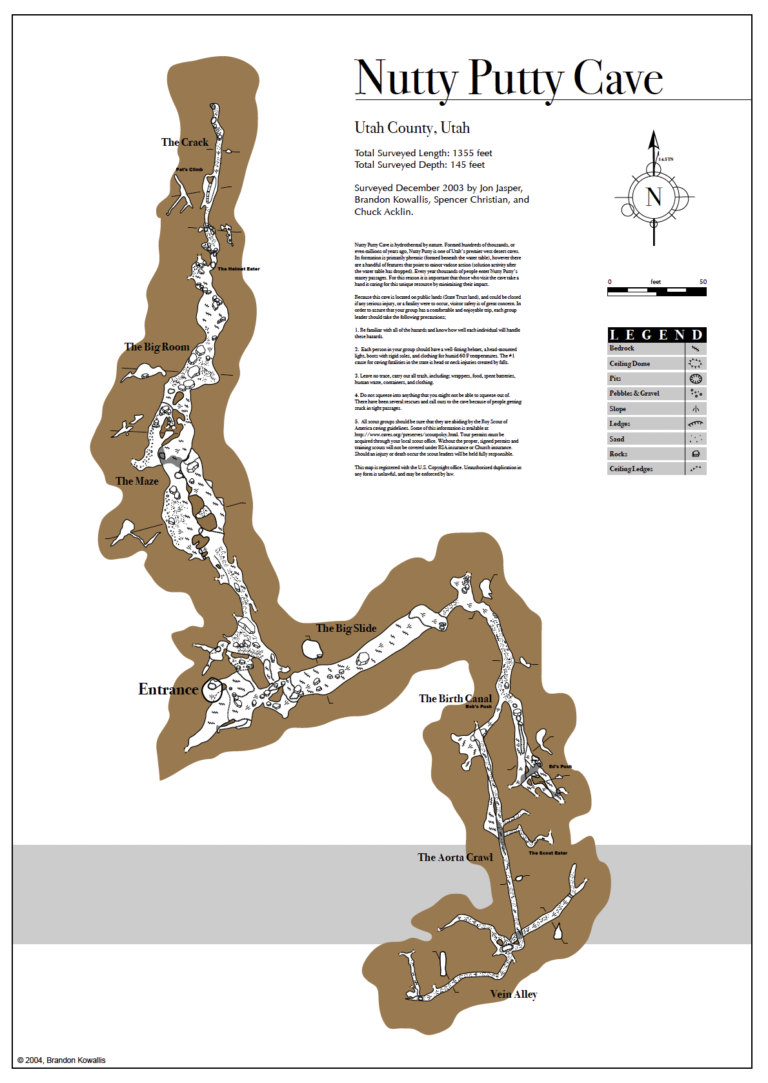

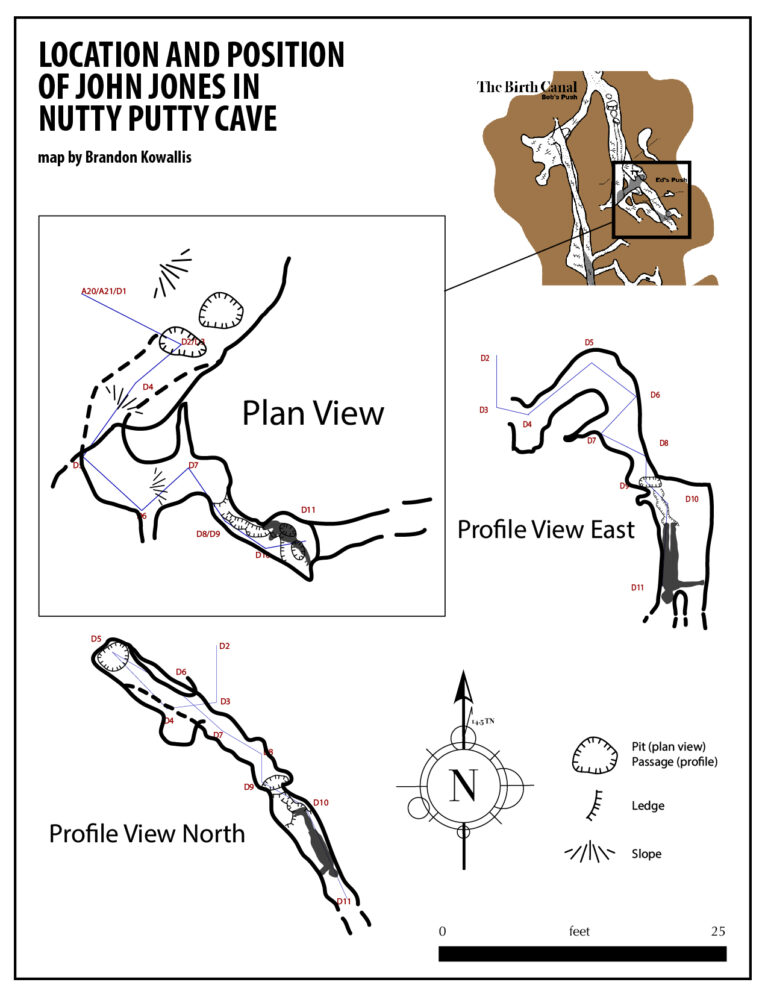

Here’s a rescue map I created after the effort to save John Jones. Back in 2003, Jon Jasper, Spencer Christian, Chuck Acklin, and I had mapped the Nutty Putty Cave, including the passage where John was trapped. Using that survey data, I made two profile views to show his location and position. I’ll also share photos from the rescue to give you a better sense of what the area looks like.

Photos from the Rescue

Map

Here is the full map of Nutty Putty Cave that I created in 2003. John Jones was actually trapped in the Ed’s Push area, not in the Birth Canal, although he would have passed through the Birth Canal to get there. If you’re interested, you can buy a high-resolution PDF version of the map for personal use here: Cave Maps.